AM ANFANG WAR DAS WORT

TO COMMEMORATE THE 500th ANNIVERSARY OF REFORMATION

More and more often we hear that we are living in times of anxiety. On the one hand, there is a threat of nuclear conflict with North Korea, and on the other hand, in some cities, there is a threat of terrorist attacks, and let's not forget about the dangers of a hybrid war that a decade have nobody even heard of. The whole situation is “spiced up” by increasingly tense discussions about sudden technological advancements in areas such as genetics or robotics. Of course, there are much more "hot topics", I just mentioned the ones that came to mind first. As you can see, we live in "interesting times".

More and more often we hear that we are living in times of anxiety. On the one hand, there is a threat of nuclear conflict with North Korea, and on the other hand, in some cities, there is a threat of terrorist attacks, and let's not forget about the dangers of a hybrid war that a decade have nobody even heard of. The whole situation is “spiced up” by increasingly tense discussions about sudden technological advancements in areas such as genetics or robotics. Of course, there are much more "hot topics", I just mentioned the ones that came to mind first. As you can see, we live in "interesting times".

As a historian (by trade), I have to disappoint all those who treat this type of perturbation as a kind of pause in periods of peace. The history of human civilization proves rather that it was the last dozen or so years in Europe that was an anomaly, something unprecedented. Normally, the reality of the Old Continent was equally chaotic and dangerous, as today, if not more so. Just look at the history of wars in Europe. After reading about them you can lose a desire to live. Our ancestors waged war with each other all the time, bringing this “art” to perfection.

I do not want to be just a bearer of bad news. The positive news in this context is that, even in these "interesting times", cultural, social and scientific life flourishes. We do not need to live in a safe bubble to be able to create, explore, and ask important questions. I will say even more: it is hard to resist the impression that humanity is in need of something endangering it. Let's take the first example: renaissance Italy. Probably no one will deny that this era in the Italian Peninsula was extremely lush both in terms of art and philosophy. It is rarely mentioned, however, that, for most of that period, the Italian city-states were in state of brutal wars with each other and with outside powers such as France and the First Reich. In spite of this, the anxieties did not interfere with Michelangelo's work in the Sistine Chapel, and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina composed dozens of his Masses, hymns and motets.

| The 500-th Reformation Anniversary

I am mentioning all this because yesterday, on October 31, we celebrated the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. In 1517 Martin Luther, a modest Augustinian from a rather provincial area compared to Rome or Paris, presented his famous theses (although he did not nail them to any door), which - as it turned out later - shook the world. As a result of the activities of Luther, Philip Melanchthon and their associates, there was a peculiar "accumulation" of important and often bloody events that forever changed the face of the Old Continent. But it was also the beginning of the necessary changes in many areas. It would be hard to list them all, so I'm referring only to one, which High Fidelity Readers will find most interesting: music.

It, obviously, did not change overnight, especially from the point of view of theoretical assumptions and their practical application. Modern scholars point out that a truly revolutionary moment in the history was the work of the Florentine Camerata, that proposed to move away from medieval perception of music, that is the love of polyphony, and to turn to the principles proposed by the ancient Greeks with the key role of monody. Me - I do not know about you – I am not a great fan of music theory. I am much more interested in the part this field of art played in the everyday lives of people - and that did undoubtedly change with the spread of Luther's teachings.

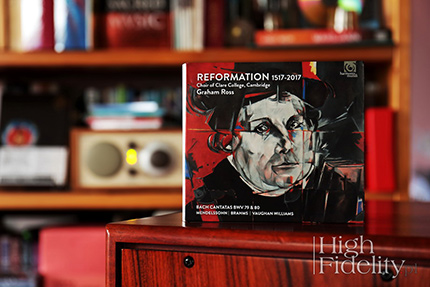

So, in order to celebrate the anniversary, after all we rarely have an occasion to celebrate any 500th anniversary, I decided to offer readers of the "High Fidelity" some information on Protestantism and music in this fraction of Christianity. It took me some time to decide how to present this topic. Finally I decided to describe the place and role of Protestant music in the lives of people in modern Europe.

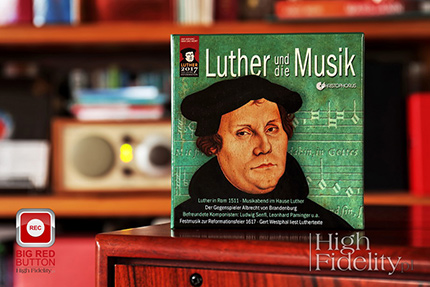

This text is supplemented by two others. The first one is an interview with Dr Rafał Szmytka, an employee of the Department of Historical Anthropology at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow, who specializes in the history of modern Europe, with a special focus on the contemporary areas of Belgium and the Netherlands. The idea is to bring you closer to the climate of that era, which - of course - also reflected clearly on the music. In the second one you will read a review of two anniversary music releases, which have been marked with a special logo of the Reformation Anniversary (Germ. reformationsjubiläum).

I hope that reading the whole thing will give you the same joy as working on it gave me. I believe that this text will be comforting to all those who are tired of living in "interesting times." These can be and are difficult, but at the same time ... interesting.

Dr RAFAŁ SZMYTKA

Department of Historical Anthropology

History Institute at Jagiellonian University in Cracow

Mr Rafał Szmytka in Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, in the background the Rembrandt's Night watch; photo: Rafał Szmytka

Few people realize that the roots of Protestantism are to be found not in Germany or the Czech, but in the Netherlands – one can refer to the Franciscan William Ockham or Gerard Groot. Why was it there where this new spirituality in the Middle Ages was born?

Devotio moderna, is the movement you're referring to, actually originates from the Netherlands - the homeland of Erasmus of Rotterdam and Thomas a Kempis, who alongside Gerard Grote can be identified as the main representative of this trend. The path for the lay societies of Friars and Sisters of Common Life founded by him, seeking the spiritual renewal of the Catholic Church has already been laid down by the secular assemblies of Beguines and Beghards , which the papacy recognized as hatcheries of the heresy. To this day Béguinages – oasis of calm from the urban hustle - can be found in the full of tourists Bruges or in Leuven. Not surprisingly, shortly after Martin Luther's announcement of 95 theses, the statements contained in them fell on the fertile ground in the Netherlands, and in 1520 the first edicts against heretics were published and a year later, the first stake was burned - this time only with books.

Historians often point to significant differences in the mentality of people in the Middle Ages and in modern times. How much influence on this change had the new faction in Christianity?

I think that in this context, the very emergence of the possibility of choosing religion, especially in areas like some provinces of the Netherlands and the Republic of Poland that offered such possibility, has played its part, and it was used it to justify people's own way of life. This is perfectly illustrated by the wealthy Dutch bourgeoisie who scrupulously collected wealth - after all, according to the Calvinist predestination, the one who succeeds will surely be saved. Similarly, the difference can be seen in the approach to helping the poor, who in the Protestant countries were to be rehabilitated through work in closed factories such as Bridewell in London or Rasphuis in Amsterdam.

Religion in the everyday life of people of the Middle Ages played a very important if not key role. How does something that today can be called "slow life" influenced Protestantism? Did it promote in some way (if so: how?) specific forms of rest? Or maybe it just focused on banning some forms of it, such as dancing?

There is no better contemporary example of slow life than Mikołaj Rej's Żywot człowieka poczciwego. We find there a whole paragraph about how much pleasure a rest in the bosom of nature or conversations with friends offer. Let us not forget that the author of this Arcadian vision of the Polish village of the mid 16th century was a true Protestant, whom Catholic opponents accused of the Church desecration calling him a "lusting Satan."

How did Protestantism influence artists, their lives and work? Did it allow - by emphasizing the freedom of every Christian - to lose the limiting corset of rules that governed medieval art? Or did it impose limitations itself, just of another kind?

Let me answer with question: can this metaphorical "medieval corset" be seen in the paintings of Flemish masters of the fifteenth century such as: Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling and little later of Hieronymus Bosch? With the passing of time, painting techniques (which Johannes Stradanus emphasized in his graphic depictions of contemporary times) and fashion changed - just look at the works of great Italian artists.

Let's get back to the Netherlands: from the late Middle Ages there a trend in painting develops that serves to initiate convivium - conversation (not only) at the table. Such was the task of Wedding portrait of Arnofilich (1434), Babel's Tower (1563) by Pieter Breugel but also of paintings by Dutch masters of the seventeenth century, such as coming from the Catholic South Netherlands Pieter Paul Rubens (Descent from the Cross, 1618) and Jacob Jordaens (King drinks, 1638) and from the Protestant Northern Netherlands such as Rembrandt (The Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburgh, 1642) and Jan Steen (Crazy Farm, 1660 ).

Luther Rose, a symbol of Protestantism; (source: Wikipedia, public domain)

What's more, artists painted what the client wanted them to - the patron or simply the person who ordered the painting according to the artist's portfolio - and let us not be surprised, because since the medieval times sculpture based on the so-called patrons, or patterns were "produced" in the Netherlands. As a result, in almost every Dutch home in the modern era one could up to several dozens of paintings of varying quality and value. These manifestations of "wealth" along with the goods flowing from the colonies contributed to the rise of the golden age myth.

European historians point to the period of Reformation as the time when proto-propaganda was born. What role did art play in it? This aspect is interesting to me particularly in the context of music, but also of painting and sculpture.

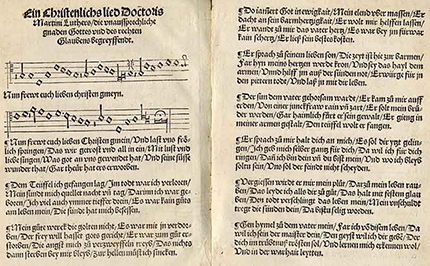

First of all, we have to talk about propaganda without the prefix "proto". In the sixteenth century, it was a well-developed field that benefited all parties of religious, social and state conflicts. It is often said that the French revolution or the industrial revolution marked the end of the modern age. In fact, it has produced several other "revolutionary" changes. One of them was the printing and the ability to spread content, written word on an unprecedented scale.

Great artists – painters and graphic artists – were involved in spreading the idea of reformation and in religious or political propaganda. Their works were reproduced as woodcuts and later copperplate engravings. These could be purchased at the markets of the Dutch cities, but also in Paris, in Bremen or even in Gdańsk within one month and most importantly - at a small price. Due to the high percentage of illiteracy among European society, iconography, on par with oral content, played a significant role. The written word should be given only a secondary role. RS

| PROTESTANTISM ABD MUSIC

Not many know this, but Martin Luther - as the sources tells us - was musically talented. And educated in music, at least to some degree. The future reformer of Christianity explored the secrets of liberal arts (septem artes liberales), which also included music. It is worth adding - because you will need this information later - that in the Middle Ages it was perceived as a science, not an art per se.

The theory of music, however, can be explored for years, and still have absolutely no talent to perform it. Dr. Luther was supposed to, however, delight people with beauty of his voice. Hans Sachs, one of the most important German meistersinger of the sixteenth century, author to around 4300 (!) religious and secular musical pieces (to which, in the meantime, he added 2,000 more poems and fairy-tales) was impressed with Luther's skills. The artist wrote even in 1523 a poem in honor of Luther, entitled Die Wittenbergisch Nachtigall. It is true that the author as fertile as Sachs could have used any topic (after all these 6,000 works had to be based on something) and significantly "magnify" Luther's talent, however, he is not the only person who succumbed to the Luther musician magic. It is worth adding that Martin Luther not only sang but also played the lute.

The Reformer of the Church was a lover of music, but also - which is even more important in our deliberations - was well aware of its power. In her article Przepędza diabła, dostarcza radości. Luter, reformacja i protestantyzm w muzyce i o muzyce (in: Pomocnik historyczny „Polityka”) Dorota Szwarcman cited - extremely poetic - Augustinian opinions on this type of art:

I love music […]. And music is, firstly: God's gift and it does not come from man; secondly: cheers heart; thirdly: drives the devil away; fourthly: it provides innocent joy. Thanks to music anger passes, temptations and pride disappear. The first place after theology I give to music.

It is not surprising, given the high position of music (the second one) in Luther's eyes, that the Protestants from the beginning treated it as something more than just a science. It was a source of emotion (not scientific excitement), but also a priceless tool: both in affirmation of the new principles of faith and in the struggle with Rome.

More and more often we hear that we are living in times of anxiety. On the one hand, there is a threat of nuclear conflict with North Korea, and on the other hand, in some cities, there is a threat of terrorist attacks, and let's not forget about the dangers of a hybrid war that a decade have nobody even heard of. The whole situation is “spiced up” by increasingly tense discussions about sudden technological advancements in areas such as genetics or robotics. Of course, there are much more "hot topics", I just mentioned the ones that came to mind first. As you can see, we live in "interesting times".

More and more often we hear that we are living in times of anxiety. On the one hand, there is a threat of nuclear conflict with North Korea, and on the other hand, in some cities, there is a threat of terrorist attacks, and let's not forget about the dangers of a hybrid war that a decade have nobody even heard of. The whole situation is “spiced up” by increasingly tense discussions about sudden technological advancements in areas such as genetics or robotics. Of course, there are much more "hot topics", I just mentioned the ones that came to mind first. As you can see, we live in "interesting times".