No. 257 October 2025

- COVER REVIEW: ANCIENT AUDIO Silver Grand Mono Mk II ⸜ power amplifier • monoblocks » POLAND • Kraków

- KRAKOW SONIC SOCIETY № 153: 30 years of ANCIENT AUDIO » POLAND • Kraków

- FEATURE ⸜ music & technology: HISAO NATSUME presents - In search for the lost great pianism Chopin tradition » part 2 (France) » JAPAN • Tokyo

- REVIEW: AUDIOPHONIQUE Classic AP 300D ⸜ power amplifier » POLAND • Pruszków

- REVIEW: AVATAR AUDIO Holophony No. 1 ⸜ loudspeakers • floor-standing » POLAND • Osowicze

- REVIEW: DIVALDI Gold PA One ⸜ integrated amplifier » POLAND • Kraków

- REVIEW: J.SIKORA Aspire ⸜ turntable (deck + tonearm) » POLAND • Lublin

- REVIEW: MB AUDIO CABLE Silver ⸜ analog interconnect ⸜ RCA » POLAND • Turza Śląska

- REVIEW: XACT N1 ⸜ LAN switch » POLAND • Wrocław

|

Editorial

text WOJCIECH PACUŁA |

|

No 257 October 1, 2025 |

|

POLISH AUDIO

GATHERING COMPONENTS FOR THE SEPTEMBER “Polish” edition of “High Fidelity” is an interesting exercise in imagination for me. There are plenty of products of this type, mature products, I might add. Some time ago, Poland mentally and competently left behind the times when we were trying to “catch up,” “make up for” and “do our homework”. At least that's how I see it.

⸜ The largest Polish manufacturer of electronic tubes during the communist era was Polamp. All these things were necessary in order to find ourselves, after the communist era, in a place where global audio perfectionism had been present for decades. And the Western companies had about fifty more years to achieve this. Let us recall that before World War II, the outbreak of which we commemorate in Poland on September 1 at 4:35 a.m., when Nazi bombs fell on Wieluń, then located near the border with the German Reich, we had many interesting projects in our country related to music reproduction, both in terms of gramo-phones and records. However, everything changed after the war, and at a time when the US and the UK were experiencing a boom and the hi-fi industry as we know it today was born, it was based on the passion and knowledge of engineers re-turning from the war, using electronic equipment that was being decommissioned, Poland entered a period of gloom, poverty, dependence and subordination to the Soviet Union and a centrally controlled economy, which quickly reached a dead end. And with it, people wanted to hear something more than the crackling of the Bambino record player.

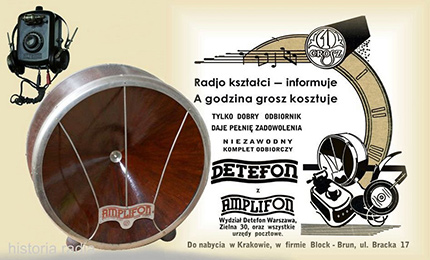

⸜ Polamp NOS tubes are currently used by AYON AUDIO in its Spirit SE amplifier, more → HERE Let us recall that before World War II, hand-cranked gramophones, radio receivers, and even vacuum tubes were manufactured in Poland. As early as 1921, three years after the end of the Great War, Radjopol, a War-saw-based company, began manufacturing tubes for the Ministry of Military Affairs. Later, in 1923, the Polish Radio Technical Society (PTR) launched the licensed production of radio tubes. The Polamp tubes, popular af-ter the war, were based on designs made before the war by the Dutch company Philips. However, all these solutions were based on licenses or were copies. Not entirely, the contribution of domestic engineering thought was present in them, but it seems that it was not decisive. Domestic devices were simple in design, such as the extremely popular Detefon, a Polish radio receiver equipped with a crystal detector, in the 1930s. It was developed in 1929 by Wilhelm Rotkiewicz, a graduate of the Faculty of Electrical Engineer-ing at the Warsaw University of Technology. The device was registered with the Patent Office under number 2198. The creator of the radio receiver described its operation and construction in detail in the monthly maga-zine “Przegląd Teletechniczny” (Teletechnical Review) in January 1931.

⸜ The Detefon could be purchased with headphones or a speaker; however, the difference in price was astronomical. I had a radio like this and used it to listen to music, mainly on long waves. Although I was born long after the war, during the “Gierek miracle period” my grandparents still had this type of receiver with headphones, manu-factured after the war by Telpod (the DT2 model was produced between 1946 and 1955). It took a while to find a crystal, but I succeeded. Although I no longer have the device itself, I still have the headphones. Crystal radio was based on a simple circuit that received radio waves using an antenna and then converted them into sound using a detector, which was a galena crystal. The receiver had no external power source; it obtained the energy it needed to operate directly from radio waves. Radio technology historian Henryk Berezowski told PAP (emphasis added):

Although Berezowski mentions headphones, in reality, the set could be supplemented with an Amplifon or Am-plifon II speaker. However, this was a much greater expense, as it cost as much as 125 zlotys. To un-derstand how much money we are talking about, let's say that for PLN 10 you could buy a piglet, and for PLN 20 a cow. A teacher's salary ranged from PLN 160 to PLN 260, and a school principal's from PLN 450 to PLN 750, which was a very large amount for those times.

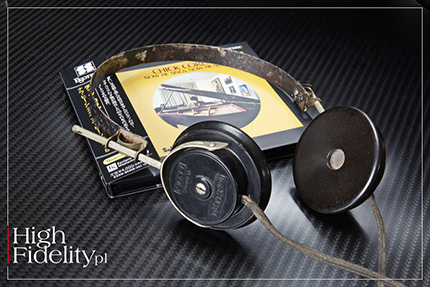

⸜ My headphones for the Detefon… Amplifon was a complete loudspeaker – as we would say today – an active one. It was powered by a built-in tube amplifier. And it looked great! I have never seen one in person, nor can I find its technical description, but it is quite likely that it used a Philips driver and perhaps also Philips tubes. The Polish contribution was the enclo-sure – a wonderful example of Art Deco. If we were to compare the post-war situation with the democratic breakthrough of 1989, we could say that they are two different worlds. We emerged from the Polish People's Republic with many excellent products – speakers, amplifiers, turntables, tape recorders (reel-to-reel and cassette), and even CD players. Some of them were manufactured under license, but most were the brainchild of our engineers. Their problem was, on the one hand, being cut off from higher-class components, and on the other, being derivative – these were all designs that had been produced in countless variations for years in the so-called “West.” |

After the political transformation, many interesting designs were created in Poland, but they were not inno-vative in any way. Every now and then, there was talk of an interesting amplifier or speakers, but it still did not result from in-depth consideration linked to scientific research. Perhaps that is why audio stores (grandly called salons) mostly stocked speakers and amplifiers, as they did not require much effort to design. However, there were very few Polish CD players or turntables, not to mention cabling, on the market. The exception was Ancient Audio, celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, whose CD players with tube outputs were a step to-wards high-end audio.

⸜ XACT N1 LAN SWITCH – this is one of the few original works of its kind in Polish perfectionist audio. It was not until the 2000s that something resembling a breakthrough in terms of quantity with a qual-itative twist occurred. Companies such as Fonica (in its new incarnation, now defunct), J.Sikora and Muarah with turntables, LampizatOr with file players, JPLAY with music playback software, and then with the XCAT brand with file transport and LAN switch, manufacturers exploring issues related to noise minimization, such as Verictum and Thunder Melody, as well as cable manufacturers – KBL Audio, Melodika, Audiomica, Soyaton, WK Audio, etc. – and those fighting vibrations, such as Pro Audio Bono, Divine Acoustics, Graphite Audio, and Rogoz Audio. A special case, because it was truly innovative, was the analog sound processor from Yayuma Audio, model → AWARNESS LINE ASP 01. However, if we take a closer look at the current offerings from Polish manufacturers, it turns out that, in reality, not much has changed. Yes, we finally have manufacturers in Poland that are known around the world, because there are also Pylon and Fezz Audio, but it's the same pattern. When looking for Polish products for the Septem-ber issue, year after year, I keep coming back to the same categories: most of them are speakers and amplifiers, there are quite a few cables, and recently also digital-to-analog converters. I have products for noise and vibration damping at my disposal.

⸜ Pro Audio Bono is a company that has developed its own method of reducing vibrations and has patented it. It's good that Polish audio is really rich in brands and solutions. But these are brands and solutions based on so-called low technologies. Perfectionist, let there be no doubt, often top-notch on a global scale, but still secondary. Where are the manufacturers of file players or SACD players? The latter do not exist at all, and there are almost no people seriously involved in file playback. The situation has not been changed by Accuhorn (more → HERE ˻PL˺), Ancient Audio (more → HERE ˻PL˺) or Audiophonique. The only Polish manufacturers that are recognized worldwide and offer truly original solutions in this area are the aforementioned LampizatOr and JPLAY under the XACT brand. One could also mention Michał Jurewicz's Mytek, but it is a US manufacturer, albeit with Polish roots. Modern and innovative are the power sup-plies from Ferrum, which are another source of pride for us. All other designs, however, repeat what has already been done, refining this or that element. Even if they are excellent, they do not meet the condition of “innova-tion.” One explanation may be the overwhelming number of such products from China. No one can com-pete with Shenzhen manufacturers in terms of price and availability. But that's defeatist thinking, as if we were lying on our backs waiting for someone to kick us in the balls because they're bigger and all that. It's impossible to compete with China on price, but it is possible to compete on quality and locality, on innovation and ingenui-ty. We have excellent engineers in Poland, and some of them like to listen to music. In addition, a small number of the latter really understand the difference between academic knowledge and detailed knowledge developed by experts, i.e., us.

⸜ One of the most interesting companies in terms of technology was Yayuma Audio • photo by Yayuma Audio It is from them that I would expect an impulse. It is not necessarily about developing entire devices, although that would also be beneficial. It is about research that would solve some of the problems related to audio. It is no coincidence that Japanese companies still – albeit much less frequently – present products based on research conducted by domestic universities, with Acoustic Revive leading the way. The adaptation and application of these ideas yield excellent results and change the sound for the better. I know, I know – you can't blame everything on a lack of knowledge and willingness. A powerful obstacle is a lack of capital. Capital that would not be afraid to invest in uncertain research and small companies. The US and Germany, which have been role models in this respect for many years, have shown that this is a good way to develop the high-tech industry, which we also use. The fact that we are lagging behind in this area is evi-denced by the almost complete lack of patents for modern audio solutions, with the exception of Pro Audio Bono, the aforementioned Yayuma Audio, and perhaps a few other manufacturers. If we want to start building innovative audiophile products, we need to change the way we think about audio and connect with the academic community. However, the academic community must first be willing to do so, and then understand that it makes sense and will translate into money. And we would need some kind of “reset” in the animosity between these two worlds. “We” would have to stop thinking of academics as “deaf people” and “technocrats,” and “they” would have to stop thinking of “us” as ‘fanatics’ and “ignoramuses”. I could say that the future seems bleak, but I don't want to end this text on a minor note.

⸜ Ancient Audio SDMusA FLASH card file player • photo by Ancient Audio There is something happening, as evidenced by the new tube factory that Fezz Audio is planning to build. But if someone were to think about a new version of the SDMusA Ancient Audio player, it would be refreshing. That no one listens to music from stationary files anymore, but only streams it? In that case, we would have to reject CDs and SACDs, because everyone is online, right? Or maybe someone would finally take a closer look at the material formula for vinyl records. It is no coincidence that records pressed in the 1950s and 1960s usually sound better than contemporary ones, even though mastering methods are now much more sophisticat-ed. The problem is that many materials that are harmful to health and made old vinyl sound better cannot be used today. Is it really impossible to overcome this issue and achieve similar results with modern materials? I don't believe so... I'm sure it's a matter of will, capability, and money. Similarly, in the case of the aforemen-tioned tubes, which today cannot be produced using the same technologies as in the past. Poland is in the perfect place at the perfect time. Never before have we had such an opportunity for growth. We have the capabilities and knowledge, and we also have the money. We only need one thing—the will to do it. And that is what I wish for all of us on this beautiful September day! ● WOJCIECH PACUŁA |

About Us |

We cooperate |

Patrons |

|

Our reviewers regularly contribute to “Enjoy the Music.com”, “Positive-Feedback.com”, “HiFiStatement.net” and “Hi-Fi Choice & Home Cinema. Edycja Polska” . "High Fidelity" is a monthly magazine dedicated to high quality sound. It has been published since May 1st, 2004. Up until October 2008, the magazine was called "High Fidelity OnLine", but since November 2008 it has been registered under the new title. "High Fidelity" is an online magazine, i.e. it is only published on the web. For the last few years it has been published both in Polish and in English. Thanks to our English section, the magazine has now a worldwide reach - statistics show that we have readers from almost every country in the world. Once a year, we prepare a printed edition of one of reviews published online. This unique, limited collector's edition is given to the visitors of the Audio Show in Warsaw, Poland, held in November of each year. For years, "High Fidelity" has been cooperating with other audio magazines, including “Enjoy the Music.com” and “Positive-Feedback.com” in the U.S. and “HiFiStatement.net” in Germany. Our reviews have also been published by “6moons.com”. You can contact any of our contributors by clicking his email address on our CONTACT page. |

|

|

main page | archive | contact | kts

© 2009 HighFidelity, design by PikselStudio,

projektowanie stron www: Indecity