|

COLUMN | PROFILE OKIHIKO SUGANO

|

|

|

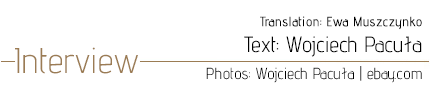

Mr Okihiko Sugano on the cover of the Okihiko Sugano Record Collection box Not accidentally, the record used for the presentation of a new motor for the TechDAS Zero turntable had been chosen by Mr Hideaki Nishikawa, the main company’s constructor. It is because it had been recorded by Mr OKIHIKO SUGANO and released by his AUDIO LAB. RECORD label – both Mr Sugano-san and his record label have the status of legends in Japan. I had known both the name and the record label, but I got rid of planks in my eyes when the grilles fell off – the owner of the Audio Lab. Record and his activity had been known to me, but only separately – I had never before looked at these elements as a whole. Motivated by this event to take some action, I decided to look closer at this story right after coming back to Poland. It proved even more fascinating than it had seemed to be and the article below was written on the basis of one-year research.

In the 1960s, Mr Sugano was the sound engineer responsible for Takt Jazz Series records. The photos shows a remaster released by Nipon Columbia on Blu-spec, the Love is Here to Stay album of the Kazuo Yashiro Trio I hope you will forgive me – even though I have made every effort, the article is full of ambiguities, white spots and incomplete information. Similarly as in the case of the article entitled Prise of a (non)format: XRCD, this time I also had to use extremely scarce information in English. In a few cases, I even used the help of my acquaintances and friends who collected information in Japanese for me and even translated longer texts – I would mainly like to thank Mr Mieczysław Stoch, Mr Yosuke Asada (“Net Audio”) and Mr Yoshi Hontai (Muson). What I have also found useful was a monumental, three-year cycle of interviews with Mr Sugano, carried out by the Japanese “Analog” magazine (available on the website of the phileweb.com publishing company). I hope that despite these defects, you will be able to take a fascinating ride without holding the reins while reading the article. | THE MAN Okihiko Sugano (Japanese 菅野沖彦), called Okie by his friends, was born in September 1932 in Tokyo. His younger brother is the well-known jazz pianist Kunihiko Sugano (Japanese: 菅野 邦彦) who records albums with the most important Japanese and American record labels. Mr Sugano’s artstic activity – as this is how he sees the art of recording and playing back recordings – can be divided into three periods, each connected with a medium that he dealt with at the given time: 1960-1969, when he worked for the Ashai Sonorama record label and the recordings he produced were released on pressed soft vinyl discs, 1968-1981, when he focused on LPs and worked for the Takt, Trio and his own Audio Lab. Record record labels, and 1983-2000, called the “digital era”.

Pict. SHINGO OKUTOMI/Ongen Publishing He was brought up in a family who owned a phonograph and several recordings, which was an exceptional thing at that time. As Mr Sugano says, even though they also had a piano at home, the family was not very “musical”, but rather “cultural”, as both the phonograph and the piano were to show their status, and not to let them enjoy music.

Takt recordings are also available in a unique form – the CDJapan.co.jp store offers “CD On Demand”, i.e. recorded on CD-Rs from files supplied by a record label. The photo shows the Terumasa Hino Concert album. Even though he was attracted by music and wanted to play the piano, his father did not allow him to do that. So, he chose technology and disassembled all the phonographs that he managed to get, including the one that they had at home, despite his father’s unavoidable anger. He got interested in sound differences after coming back to Tokio from Sado where he had spent the last years of the war. Due to frequent power breaks, he was not able to listen to the radio as often as he wanted to. When he could not do it, he listened to a manual turntable which sounded different from what he heard on the radio. He assumed that it was a defect of the needle and decided to do something about it. In this way, he combined his interest in the mechanical aspect of recordings with music itself. So, his professional work has always been connected with sound engineering, as well as journalistic and educational activities. As a student, he attended lectures on music at the Tokyo University of the Arts and took singing lessons. He passionately read everything on music and music reproduction equipment. However, already at that time, he dreamt of having his own record label, as well as of an audio magazine that would combine music and sound. So, he founded such a magazine with his friends – nobody had heard about “audio” at that time, so the title of the magazine referred to the radio. Alongside editing the magazine, together with people such as Shunsuke Wakabayashi who was working at a radio station at that time, he also founded a record company called Metronome Record that was to release vinyl records.

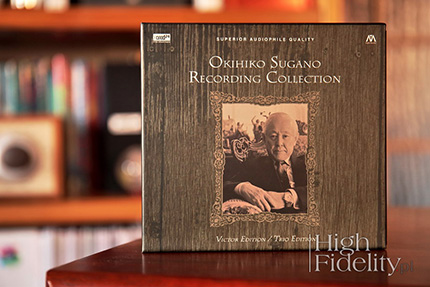

Mr Sugano began his work in the 1970s by making records for the Trio Records label. The photo shows Kazuo Yashiro’s Drivin’ album They managed to release a few records together, but when Mr Sugano got a job offer from an American who was in charge of his company branch in Japan, he accepted it and left music aside. However, he could not live without it and, after three years of voluntary “exile”, he became the editor-in-chief of Asahi Sonopress. It is part of the Asahi Shimbunsha publishing company, established in 1959 to record interviews, news, crime reports, etc. Their recordings, pressed on soft vinyl discs, were attached to their printed publications. While working for the company, Mr Sugano dealt with, literally, everything: recording, editing, mastering, pressing and graphic art. He also met Japanese musicians, both jazz ones and those performing classical music, which proved useful in the later years of his career. As he says, he learnt everything about sound and analogue recordings there and became ready to be a freelancer. The first of his own records were created in 1968, when he did a brilliant job for the Takt record label, making records that were re-released some time ago on Blu-spec CDs by Nippon Columbia as part of the “Dig Deep Columbia” series. Ampex tape recorders dominated the audio industry at that time and he used them at work. Neumann microphones were most often used at studios, but Mr Sugano preferred the Altec M50 microphones.

Mr Sugano often published for his parent magazine “Stereo Sound”, both as the host and a guest As he said in an interview for the philweb.com portal, part of the Ongen Publishing Co. Ltd., a very big problem that he had at that time was finding a suitable system that he could use to listen to music at home (more HERE). When he worked for Sonorama, he used the Diaton 2S – 305 monitor speakers, then the Altec 605 B, with a large woofer and a concentrically located horn of the mid-tweeter. However, he chose a JBL system, which he still keeps, to use at home. | THE SYSTEM Okihiko Sugano is not only known for his work connected with sound engineering, but also for many years of working as an editor for audio magazines, mostly for “Stereo Sound”. He reached the position of a “Senior Reviewer” there and was the host of a cycle consisting of a few dozen episodes, in which he visited Japanese music lovers and audiophiles at their homes. They listened to music, discussed matters connected with equipment, art and hobby together, and he published reports on these matters in the magazine. Mr Sugano’s incredible knowledge of audio products, electronics, acoustics and recording techniques made him become an oracle on audio systems. His own system was also discussed and commented a lot of times. Mr Sugano’s system in its present form was described in issue 151 of “Stereo Sound” (2004). It is based on two sets of loudspeakers. The first one is a JBL system consisting of an enormous housing with two very large 2205 A low frequency transducers (38 cm in diameter each) and the 375 compression driver with a 4-inch membrane situated on their housing, and the original version of the “acoustic magnifying glass”. There are also the GEM TS208 tweeters supporting the operation of the system, located on the horizontal case and the Muon TS001 super tweeter. From the bottom, the JBL speakers are supported by the Yamaha YST - SW 1000 L subwoofer. However, yet another transducer is the most noticeable – the German Physiks DDD Troubadour 80 omni-directional transducer, supporting another loudspeaker system. German Physiks really owes a lot to Mr Sugano, as it was enough for him to say one word to decide whether a product would enter the market or not: The person who is largely responsible for launching the Unicorn model is Okihiko Sugano, the main reviewer of the largest Japanese hi-fi magazine entitled “Stereo Sound”. During a visit at a German Physiks factory, he noticed its prototype and was not deceived by its coarse look. He listened to it and strongly suggested that it should enter the market as a legitimate product. The company almost instantly followed his advice and this is how the success story of the loudspeaker began on Asian markets. The transducer supports another amazing system: the two-piece McIntosh XRT 20 loudspeakers. They consist of two elements: a woofer system in a rather classic housing and tweeters forming a so-called line array. While the woofer is placed on the floor, the line is suspended flat on the wall. Okihiko Sugano and McIntosh

So, it was natural that he wanted to meet the people who had been responsible for these devices. Roger Russell, the director of the Acoustic Research Department at the McIntosh Laboratory, Inc. and the originator of loudspeakers produced by the company, recalls that it was very difficult to go to the USA at that time – Mr Sugano first got there in 1967. Then he met Gordon Gow and Frank McIntosh (more HERE). However, eleven more years had to pass before either of them could go to Japan. The country was gaining importance, so it was natural for Gordon to go there in 1978. One of the reasons for the visit was a need to find a reliable partner who would make turntable cartridges for McIntosh. Mr Imamura, the director of Mark Corporation which manufactured MC cartridges was Okie’s friend then. Mr Sugano’s wife – an artist and a sculptor educated in Denmark, who, similarly to her husband, passionately smoked a pipe, made housings from brier wood especially for the company. Her teacher had been the well-known Danish artist, Ms Anne Julie Rasmussen. She had not only taught her student specific methods of work, but also made her develop the abovementioned addiction… Contacts were made and contracts were signed, and Mark Corporation started manufacturing two cartridges designed by Mr Immamura for McIntosh, the MCC800 and MCC1000, in 1984. Mr Sugano was responsible for the organization of the whole process – production planning and export, inventing the names, and sound. Unlike other MC cartridges from that period, the MCC800 and MCC1000 did not show any frequency response peak, which made them sound much more natural.

Electronic devices occupy, literally, almost the whole listening room. There are Accuphase and McIntosh preamps, a dCS SACD system, Studer A730 CD players and McIntosh MCD1000 CD transport, as well as a reel-to-reel tape recorder and headphones. However, the turntable seems to be the most important element, as it is the format that is closest to Mr Sugano’s heart. The really beautiful and majestic Thorens Reference turntable which weighs 90 kg, with the SME 3009R Gold, Series V and EMT 929 arms, occupies the central position. | AUDIO LAB. RECORD He has had love for vinyl in his blood. Although he founded the Metronome Record label already in his youth and then, at the time when he was working for Asahi Sonopress, he oversaw the whole process of creating records , his dreams had not come true until 1969, when he established the Japan Audio Laboratory record label which was renamed Audio Lab. Record in 1971. Although I highly value the records he has made for Takt, Trio Records and other Japanese record labels, his own record label that I am talking about could be the only pretext for me to write this article. Thanks to it, he became commonly recognizable and valued in the audio industry – both professional and oriented at high-end.

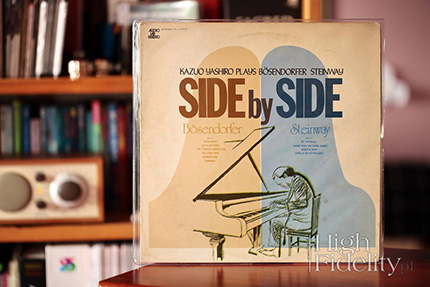

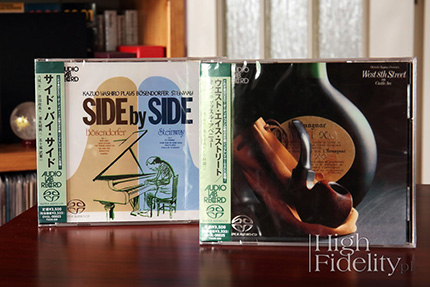

One of the most important albums for Mr Sugano: Kazuo Yashiro Trio’s Side by Side where one side was recorded with a Bösendorfer piano and the other one with a Steinway piano. It is a recording that is not typical for this record label, as it was recorded using an Ampex and not a Scully tape recorder In this way, Mr Sugano contributed to the kind of audio revolution that has been taking place in Japan since the beginning of the 1970s. Let me remind you that the Denon company released the first LP with digitally recorded material in January 1971 (more HERE). These changes gave rise to establishing such record labels as Three Blind Mice and Audio Lab. Record itself. They mostly focused on jazz music (TBM) or both jazz and classical music (ALR). They shared a high ethos concerning the method of recording, mixing and releasing records. They developed their own methods and both had the status of “analogue” companies, as although TBM offered digitally recorded albums in the 1970s (e.g. Greensleevees), they mainly released records on analogue discs and, occasionally, on tape. |

Each of these record labels also had its own group of performers. Mr Sugano’s record label recorded the music of such jazz artists (known in Japan) as Eiji Kitamura, Kazuo Yashiro, Kohnosuke Saijoh, Yuzuru Sera and Norio Maeda, but perhaps more frequently, which could have been expected, recorded the albums of his brother, a renowned pianist, Mr Kunihiko Sugano. The people responsible for the sound of TBM records were its founder and producer, Mr Takeshi “Tee” Fuji and a sound engineer, Mr Yoshihiko Kannari. The “sound” of records released by Audio Lab. Record is the fruit of Mr Sugano’s work - not in the role of an audio engineer, but a so-called “mixer”, i.e. a person responsible for live mixing of sound coming from a few microphones during a studio recording. How to record In order to explain this, it is worth looking closer at, at least for a moment, the methods of recording that were used at that time. From a historical perspective, the first records were mechanical and monophonic, and since the 1920s they were electrical, but still monophonic. The first stereophonic records come from the 1940s, but they have been sold only since 1955, when EMI presented stereophonic tape for consumers. In 1957, the stereo era really kicked off as the first two-channel LPs entered the market.

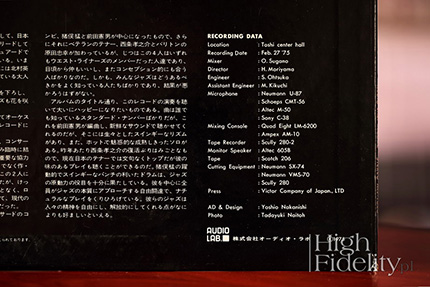

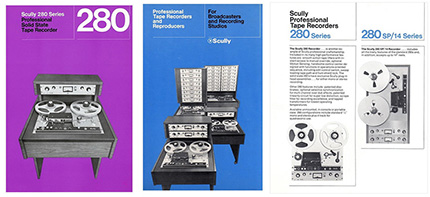

Each record released by Audio Lab. Record has an “identification plate”, i.e. the names of people involved in creating its sound and a list of the microphones and devices used. In some cases, they also feature an explanatory figure showing the arrangement of musicians and microphones The first records were made in the following way: a single microphone was placed at the centre and musicians were situated around it. The next step was to use a few microphones – signal was mixed live and recorded monophonically, and (in reality), since the second half of the 1950s, also stereophonically. The world changed when the first multitrack tape recorders appeared – first 4 and then 8, 16 and 24-track ones. Since that time, sound engineers have been able to record each instrument – or a group of instruments – separately, correct chosen fragments by recording them again and combining them with other tracks, etc. The technique reached its peak in the 1970s when it was thought that the more tracks, the better. It is commonly thought that although such recordings artistically contributed something new and fresh to music, they almost caused a catastrophe because of their sound quality. It is no coincidence that mono recordings from the years 1954-1960 and stereophonic recordings from the late 1950s and early 1960s are so highly valued. The thing is that signal went through a minimum number of devices and the master tape was ready straight away. The more microphones, tape generations and devices, the worse the sound was. And so we return to Mr Sugano. As he was not the main sound engineer working on the records that he released, he recorded directly onto a stereophonic tape recorder. These were multi-microphone recordings, but mixed live instantly onto two channels. The owner of Audio Lab. Record did not use a classic mixing table, but two eight-channel devices used for mixing outside the studio – first the Ampex AM-10 and then the Quad Eight LM6200. So, such a method would resemble direct-to-disc recording of music onto a LP. It was a “live” performance each time, i.e. everyone had to perform together and signal was instantly mixed onto a master tape. The advantage of such a method was that one tape generation was skipped – signal was instantly recorded on a stereophonic master tape. Until today, this has remained the most difficult method of recording that is only used by few, as it reveals all shortcomings of the musical technique and requires special skills from the person who mixes signal from microphones. Recordings released by Audio Lab. Records were made using two types of tape recorders: until 1975 it was mainly the Ampex AG-440 B that the owner of the record label had already used at the times of Takt and Trio, while since 1976 it was mainly the Scully 280-2, but not only. Choosing the Ampex tape recorder in the early 1970s was perfectly clear – it was a well-known brand in Japan and the tape recorder itself was really very good. However, it was the Scully 280-2 that Mr Sugano finally chose for recording and that he has remained faithful to. Why such a change? I am not sure, but perhaps it was because of some specific features of the machine, its special sound. | Scully 280

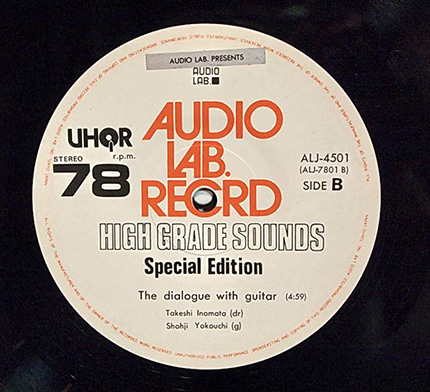

One of the demands of that period was also to make multi-track recording possible. So, Scully aggressively entered this territory by proposing a two-, three- and four-channel version, adapted for working with ¼” tape, and an 8-channel version with 1” tape in June 1966. The tape recorders were labelled as, respectively, the 280-2 (stereo), 280-4 and 280-8. In 1987, after Scully was acquired by Dictaphone, 16 and 24-channel versions also entered the market. Scully tape recorders were very popular and they can be found in the background of many photographs presenting top musicians from that era. At the Electric Lady Land Studios, 4-channel versions were used by Jimi Hendrix, while The Rolling Stones used an 8-channel version of the Scully 280-8 (Muscle Shoals Sound Studios), similarly to musicians from the Stax Records studio. In the 1970s, the company’s best stereophonic tape recorder, the 280B model, was created. Unfortunately, the firm already had to compete with Ampex, Studer, 3M, Tascam, Otari and other Japanese manufacturers at that time, because of which it was closed down soon afterwards. It returned for a moment in the 1980s with the perfect LJ-10 and LJ-12 tape recorders. However, it was the company’s swan song. More on: museumofmagneticsoundrecording.org | WHAT IS MOST IMPORTANT Mr Sugano used the basic stereophonic 280-2 model for recording music and the 280 model to cut acetate. However, it is necessary to mention a few exceptions. His flagship project, the Side by Side album, was recorded using the Ampex AG-440 B tape recorder that he had already dealt with while working for Trio Records. He released the material that he recorded on LPs, both 33 1/3 RPM and 45 RPM, and not only – one of the most wanted discs is a special version of the 78 RPM microgroove disc. The disc was pressed by the JVC manufacturing plant using UHQR, i.e. Ultra High Quality Record technology, originally developed for Mobile Fidelity Audio Lab. Importantly, it is emphasised that Mr Sugano did not take part in mastering onto the 78 RPM disc.

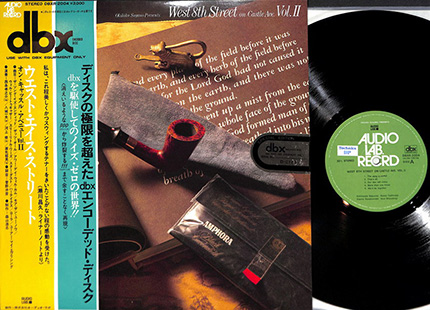

45 RPM? – Of course, it is better sound. But why not yet faster? – The answer to this question was the 78 RPM disc with tracks from the The Dialogue album; photo: ebay.com Although 45 RPM discs were then regarded as much better than 33 1/3 RPM discs in Japan, the rest of the world needed many more years to notice the simple correlation that the faster a disc turns, the smaller the distortion is. So, Audio Lab. Record went all the way and made a very difficult pressing with a yet faster-turning turntable plate. There was only one track on each side. It is worth adding that a few albums were also released on 38 cm/s reel tape. Since 1968, Mr Sugano was involved in quadraphonic records that he then enhanced by adding QS coding, compatible with stereo systems – e.g. Katin Recital with Schubert’s music. Mr Sugano talked a lot about this technology in the “Billboard” magazine from 23rd April 1974. It is one of a few cases when the main tape recorder was a four-track Ampex machine. However, it is commonly regarded that versions mixed by Mr Sugano to stereo without using the QS coder are much better. It is worth writing a separate chapter on using the dbx 122 noise reductor creatively. It is a device which intelligently reduced dynamics when signal was recorded onto a tape recorder and increased it during playback. Thanks to it, much lower noise was obtained. It was designed to be used at recording studios with tape recorders, but a few dozen LPs coded in this way were also released – including a few from the Audio Lab. Record label. One needs a dbx decoder to ensure their proper playback. They are also the most expensive and offered for 200 USD each on eBay.

Another innovation that the Audio Lab. Record used in its own way – LPs encoded in the dbx system. One needs a special decoder to play them, but they offer much lower noise and less crackling than standard discs, at the cost of slightly changed dynamics of a recording; photo: ebay.com From among discs released by the record label, it is worth paying special attention to a few titles, especially highly regarded by Japanese collectors, but also by Mr Sugano himself. These are, in the first place, The Dialogue album from the year 1977 with the music of the drummer Takeshi Inomata and his guests (ALJ-1059) and three albums entitled Side by Side. Kazuo Yashiro Plays Bosendorfer & Steinway (ALJ-1042, ALJ-1012, ALJ-1047), where the pianist plays a Bösendorfer piano on one side and a Steinway piano on the other side. Albums with classical music, such as Okihiko Sugano Presents Pierre Buzon (ALP-1039) and Pierre Buzon’s La Vie (ALP-1039) are also important. | The whole rest His experience and skills have also been used by other companies, releasing something like “Best of…” for their clients, e.g. Sony, Yamaha, TACT, Pioneer, Victor and RCA. A very important position among the albums that he has released is the 5-disc Sun Bear Concerts album with Keith Jarrett’s concert (with a sixth bonus disc in the CD version). The concert was recorded in November 1976 in Japan together by Mr Okihiko Sugano and Shinji Ohtsuka for the ECM record label. Let me add that the title was proposed by Mr Sugano.

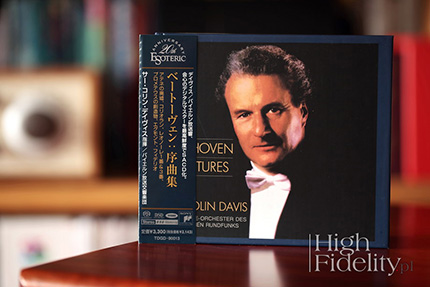

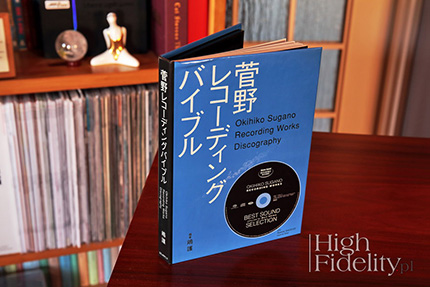

The Beethoven Overtures SACD with the recorded performance of the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks was mastered by the Esoteric company under the supervision of Mr Sugano Contemporary times have given rise to creating a few equally important re-editions. The first one is the Beethoven Overtures album with the performance of Symponieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks under the baton of Sir Colin Davis, digitally recorded for Sony. The Esoteric company prepared its new version to celebrate the firm’s 20th anniversary and its remastering was overseen by Mr Sugano. A beautiful 4-disc box entitled Okihiko Sugano Record Collection was released in 2012 in his latest Audio Meister record label on XRCD24 (XRCG-30025-8). There are digitally remastered recordings of Janos Starker, Aurele Nicolet, Meiko Miyazawa and Amadeus Webersinke from the 1970s. What is interesting, the glass masters have been made using the HR Cutting technology, originally developed for SHM-CDs. There are also, of course, albums that have been released in the course of many years by Mr Sugano’s parent magazine, i.e. “Stereo Sound”. They include both Philips records chosen by the master and a disc containing his best recordings, released with a catalogue of his records entitled Okihiko Sugano Recording Works Discography (SSSA1). These are hybrid SACDs. It is an especially important position, as Mr Sugano’s discography and a description of his work were published alongside the disc.

| AUDIO LAB. RECORD RE-EDITIONS In his pursuit of perfection, Mr Okihiko has made use of all novelties, including 45 and 78 RPM discs, and quadraphony. He also approached tapes but remained faithful to stereophonic LPs. So, it is really interesting that vinyl re-editions of his records were released only at the time when he was present in ALR, i.e. until 1979. So, all contemporary re-editions of his records are digital. Originally, his records (about 50 titles) were released on CDs by Crown Record. However, what counts on the market are only later re-editions on SACDs. Released by Octavia Records Inc., they appeared in two stages – in 2001 and 2012. Why the SACD? On 13th February 2001, the Pioneer company announced in its bulletin that Mr Okihiko Sugano became “a special member” of the group called 1-bit Audio Consortium established by the Waseda University, and Sharp and Pioneer companies in order to promote “Next-Generation Audio Technology”, i.e. 1-bit DSD (more HERE). For Mr Sugano, DSD was something that could replace vinyl. The discs have been extremely carefully prepared. The King Segikuchidai studio under the supervision of Mr Tomoyoshi Ezaki, cooperating with Mr Akira Ando and Kuniaki Takahashi, was responsible for the remaster which was made in October/November of the year 2000. Knowing the specific character of PCM DSD signals, which differ with regards to the demands that they pose and the attitude they require, Mr Ezaki-san decided to separately remaster the CD and SACD layers.

The best digital re-editions of records made by Audio Lab. Record were released by the Octavia Records Inc. record label. These SACDs are prepared as carefully as the original recordings He chose the Sony PCM 9000 recorder to record 24-bit master PCM signal and another Sony prototype (!) recorder for DSD signal. I do not know if you remember, but the PCM 9000 was a magneto-optic recorder, used by the JVC company as the “master” recorder for its XRCD recordings. By 2000, it had not been manufactured for a long time and it had been considered “obsolete”. There must be something special in it, however, since two different companies, equally fanatically devoted to sound, used the same device. The PCM layer was converted using A/D dCS 904 converters, while the D/A 954 converter and 972 upsampler were used for listening purposes. The Sony IS-1000RS converter was used for DSD signal. During recording, Sinano HRS Series voltage conditioners and Cardas Golden Cross cables were used. The only departure from the original assumptions was the fact that the Studer A80 tape recorder and not the Scully 280 was used to play the original master tapes. Let me add that Mr Sugano did not take part in the process of their creation. | Salut! Mr Okihiko Sugano-san is already very old and has not appeared in public for many years. His last public photos that I have seen were taken in 2005, while the last photos taken at home are from the year 2013 (“Stereo Sound” 186, 2013, Spring). His last records made in the digital domain were created in 2000 – these were records for the Jazz Plays Standards set.

Pict. SHINGO OKUTOMI/Ongen Publishing Despite this, he is very well known and remembered. He is one of the most important figures on the Japanese and global audio stage. He is a collector of miniature car models and 10-inch shellac records, a passionate pipe smoker (a pipe is presented on the covers of a few of his albums), a sound creator who belongs to the group of the world’s top specialists in the field and an incredibly warm good man. A legend. Shuhei Hosokawa and Hideaki Matsuoka, who presented him in the book entitled Sonic Synergies: Music, Technology, Community, Identity, wrote: The audio critic Okihiko Sugano invented the concept of rekôdo ensôka (‘record-playing artist’). His implication is that playing an LP or CD is much less concerned with mechanical reproduction than with technological creation analogous to the work of an orchestral conductor (as a classical and jazz lover, he does not allude to DJ practices). Both of them create the music not through playing the instrument but through a baton or buttons (Sugano 1991, 2005). Opposing the soft-claimed superiority of live performance, he intends to raise the acts of (re-)playing and listening to the position of high art. |

main page | archive | contact | kts

© 2009 HighFidelity, design by PikselStudio,

projektowanie stron www: Indecity

perfectly remember the moment when grilles covering the woofers of the

perfectly remember the moment when grilles covering the woofers of the