|

TECHNOLOGY/MUSIC ⸜ digital recorders DENON PCM ⸜ p. 2

1972-1974 |

|

TECHNOLOGY

text by WOJCIECH PACUŁA |

|

No 258 November 1, 2025 |

WHEN WE START READING the Wikipedia entry on digital recordings, we will notice that a large part of it concerns the efforts related to the development of the PCM encoding system, the first attempts to use it, etc. There is also a lot written about the 1980s and a little about the 1990s, but the main body and axis around which we orient ourselves remains the 1970s.

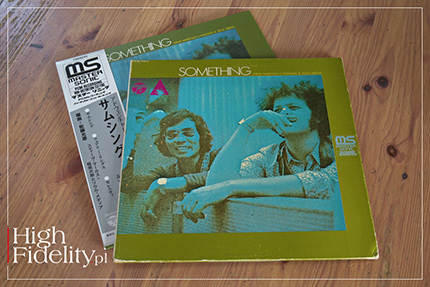

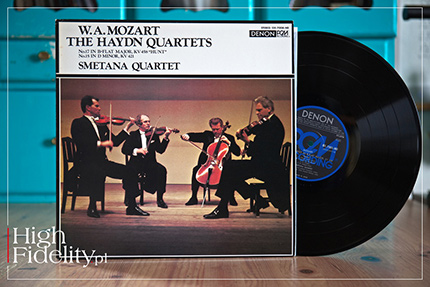

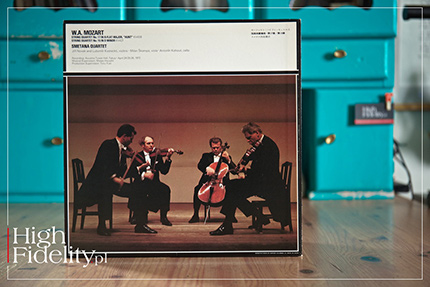

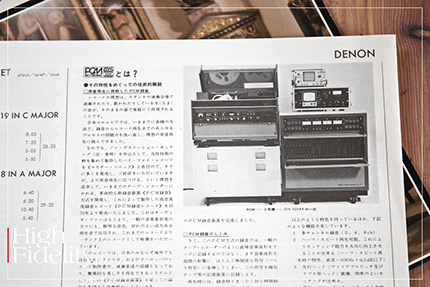

⸜ The three most important technologies used by Denon in the 1970s in the production of LP records: PCM digital recording, Master Sonic, and Non-Distortion Cutting This was a formative period for digital audio technology and, at the same time, a time when the best-sounding recordings of this type were made, perhaps with the exception of the best DXD and DSD recordings to date. It was a time when the most money was invested in this technology and recordings were made in the most purist and careful manner. And at the heart of this center, in the eye of the storm, as we might call what was happening around “digital” at the time, mainly in Japan, but also in the US and Europe, is Denon. Let me invite you to take a look at the DN-023R tape recorder, the second machine of its kind in the history of phonography, along with more details about the experimental NHK tape recorder that preceded it. To verify the technical issues, we will look at three vinyl records: the world's first LP record with classical music recorded digitally: ˻ I ˺ W. A MOZART, The Haydn Quartets, wyk. Smetana Quartet, Nippon Columbia OX-7008-ND » 24-26 April 1972 ˻ TECHNOLOGY ˼ ˻ I ˺ MAGNETOFON NHK » 1970 AS WE READ IN THE HEADING of this part of the story about Denon's digital systems, it was the Nippon Columbia logo that appeared on the world's first LP record with a digitally recorded signal; find more about the record → HERE. Recorded in November 1970, when American jazz saxophonist Steve Marcus visited Japan for the second time to participate in the Newport Jazz Festival in Tokyo, it was created on an experimental digital tape recorder developed by NHK Science & Technology Research Laboratories (STRL, or NHK's research division (Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai), the state television broadcaster. It was the final chord in the efforts of local engineers, who presented their first, still monophonic machine in 1967.

⸜ NHK experimental tape recorder from 1970 • photo press release NHK According to the company's official website, encouraged by the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, the Japanese government and private industries aggressively invested in research and development related to broadcasting technology. This impetus led to the growth and development of the domestic broadcasting industry. For example, satellite broadcasting was developed, followed closely by color broadcasting. And further:

As George Petersen writes elsewhere, the development of this first experimental NHK tape recorder cost 3-4 million yen (approximately $12-16 million today). The project was led by Kenji Hayashi (former head of the Consumer Products Research Center at Hitachi Ltd.), who oversaw the development of this technology at NHK. He collaborated with dr. Heitaro Nakajima, who in 1955 developed, among other things, a prototype of the first Japanese condenser microphone, the Sony C-37A. In 1971, he moved to Sony, where he developed a prototype of a multi-track digital tape recorder (1972!), and many years later he led the work on the compact disc. Three years, in 1969, and millions of yen later, the device used to create the Something album was ready. It was a two-channel tape recorder, and the 13-bit signal was recorded on a VCR recorder in stereo on 2-inch tape, with a sampling frequency of 47.25 kHz. It was a tape recorder on which no editing could be done, and recordings had to be made from start to finish, as with Direct-cut LPs. Anyway, this technology was also developed in Japan in the late 1960s, so Nippon Columbia engineers had experience with this type of approach.

⸜ The world's first album with digitally recorded material: STEVE MARCUS + J. INAGAKI & SOUL MEDIA Something, released in January 1971; In front the original edition, below a re-issue from 2020 The first three “digital” records in the history of phonography were recorded on this prototype NHK tape recorder, after which the technology was passed on to Denon engineers; previously, engineers from the record label were responsible for sound production, while engineers from NHK were responsible for the technology. This is confirmed by Tom Fine, author of a seminal article on early digital recordings, The Dawn of Commercial Digital Recording, who writes in summarizing the documents from Denn's presentations at AES conventions that Denon used its own technologies and those of NHK to “test various PCM methods” before developing its own tape recorder, and “in the early 1970s, about 20 test albums were recorded.” Interestingly, the NHK tape recorder was actually portable, something Denon would not achieve until 1974 with the DN-023RA model. It looked a bit like a Christmas tree – three modules with electronics were mounted on a vertical rack, with the tape recorder on the bottom shelf. Unfortunately, the device has not survived to this day (at least nothing is known about it) and was probably dismantled and “cannibalized” for tests that Denon was already conducting in-house. So these first three published recordings, as well as others that never saw the light of day but which we know were made, will forever remain enchanted in the master tapes, because there is no way to play them back. Their only witness is the LP records. ˻ II ˺ Denon DN-023R » 1972-1974 THE CIRCUMSTANCES surrounding this transfer of technology from NHK to Denon are unknown, as is the exact nature of the technology itself. What is important is that two years later (after the first published recording), in 1972, the first tape recorder branded by Denon, DN-023R, was ready. It can be assumed that Denon based its own machine on the NHK device, but used its own electronics – a PCM converter and analog-to-digital (for recording) and digital-to-analog (for playback) converters – and a different tape recorder. The tape recorder was different, it was a Hitachi VCR, and it was much larger and heavier than the one used by NHK.

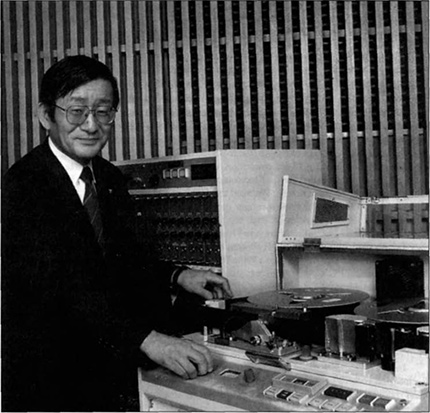

⸜ DN-23R tape recorder, the first Denon’s digital tape recorder • photo press release by Denon Czytamy:

I always claimed that it was smaller, but as it turns out, I was wrong. It was the DN-023R that turned out to be a real “beast.” The whole thing weighed 400 kg, and a single hour-long tape reel weighed 10 kg and cost over $500, which is $3,890 in today's money (according to the CPI Inflation Calculator). So it was only suitable for stationary recordings in Japan, and that's how it was used for two years. The device was both a recording and mastering tape recorder. It offered up to eight channels (8/4/2), and the operator could choose how many channels to use. The sampling frequency was 47.25 kHz, and the bit depth increased from 12 to 13 (without pre-emphasis). Perhaps most importantly, this system allowed for tape editing, hence the name „mastering tape recorder”. This was possible because the tape with the digital signal, recorded as white dots on a black background in the image section, also had an analog track for the sound accompanying the image. When recording, the signal was recorded on both simultaneously. The LP record was cut from the digital signal, while the analog signal was used for listening and correcting the width and depth of the track. Let's return to Mr. Anazawa's memories once again:

Denon presented the technical basis for the DN-023R tape recorder at the 47th meeting of the Audio Engineering Society (AES Convention), which took place in Copenhagen. The materials from this presentation, signed by the company's engineers, Mr. Hiroshi Iwamura, Mr. Hideaki Hayashi, Mr. Atsushi Miyashita, and Mr. Takeaki Anazawa, were published in September of the same year; the latter, let us recall, was the sound engineer on the album Something.

⸜ Mr. TAKEAKI ANAZAWA next to the Denon DN-23R • photo press release by Denon The materials emphasized that the Denon tape recorder was based on a studio-quality video recorder (Hitachi 4-head open-reel broadcast videotape in low-band – black & white – mode that was cheaper & had fewer dropouts than colour), explained engineering issues, and provided data on the quality of the recordings. They also pointed out its use in mastering albums with “unprecedented fidelity.” The same document also includes an entry stating that the first commercial recording made on the Denon DN-023R system was by the Smetana Quartet performing Mozart's works, recorded in April 1972 at Aoyama Tower Hall in Tokyo: String Quartet No. 15 in D minor, K. 421 (417b), String Quartet No. 17 in B flat minor, K. 458 ‘Hunt’. At least six other digital LPs recorded by Denon will be released in October, including jazz, classical music, and traditional Japanese music. To understand why musicians from what was then Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia) appeared on a Japanese recording, on what was then the most expensive product from an electronics company, on equipment that was a tour de force for 1970s electronics, and in Japan of all places, we need to go back again to the late 1960s. As Róbert Sipos writes in his review of the digital recording of Antonín Dvořák's symphony, Nippon Columbia signed many contracts in the 1960s to release albums with foreign partners. These included the American labels Columbia and Erato, the Czech label Supraphon, as well as the Polish labels Polskie Nagrania “Muza,” Box, Everest, Hispavox, and others. Columbia's rights were later transferred to Sony, and Erato was bought by RCA (now Warner), which narrowed the Japanese publisher's options for cooperation with the largest companies:

Interestingly, the official website of Supraphon states that the label's collaboration with Nippon Columbia (Denon) began in 1985 with a contract for the co-production of digital recordings, after Denon “appreciated the quality of Supraphon's recordings when recording Gold Discs for Dvořák and Smetana's albums” in 1984. The partnership included Denon supplying digital recording equipment in Prague, which led to the co-production of albums and the release of the first CDs under license from Nippon Columbia in 1986 and the first Supraphon CD in 1987.

⸜ Several units of the Denon DN-23R tape recorder were produced, differing in details; some of them are still in working order and are presented at special shows and exhibitions. • photo press release by Denon As Sipos adds, the Czechoslovakian Supraphon was not known for its high sound quality in the Eastern Bloc countries in the 1970s and 1980s. In Japan, however, it was perceived differently. Thanks to recordings co-produced by Nippon Columbia-Supraphon and Supraphon records released in Japan, a small cult developed around Supraphon. Of course, this also required the wonderful Czech performers and orchestras of that era. This was particularly important for the first album recorded on DN-023R – an album featuring a string quartet. Mr. Takei Anazawa writes that at that time, string quartets were a type of music that traditionally required ensembles to perform with exceptional precision (unlike, he adds, jazz, flamenco, Argentine tango, and percussion ensembles), and it was impossible to obtain the performers' consent to release the recording without editing. The editing option in Denon tape recorders was therefore invaluable and it paved the way for the company to enter the European and then the US markets; it was performed using a microscope, which was tedious but feasible. On the other hand, only eight tracks with small ensembles were not a major problem, even though 16-track tape recorders were the standard for analog recordings at the time. One of the characteristic features of the DN-23R tape recorder was its weight. At 400 kg and with three large cabinets, the device could not be transported. And Denon wanted to record digitally not only in Japan. This need gave rise to the much smaller, portable DN-23RA tape recorder. It was a much more compact machine in terms of both the drive and the electronics used. However, that is a completely different story, which we will return to in the third part of the article. ˻ MUSIC ˼ ˻ I ˺ W. A MOZART The Haydn Quartets Performed by Smetana Quartet

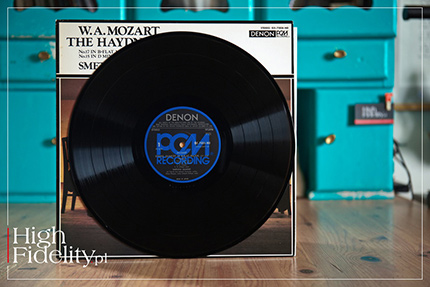

The ALBUM WITH HAYDN QUARTETS was recorded over three days at the Aoyama Tower Hall in Tokyo – April 24-26, 1972. The same repertoire was recorded again ten years later in Prague, also on a Denon digital tape recorder, but this time a DN-23RA. Masao Hayashi (林 正夫) was responsible for the sound on behalf of Nippon Columbia, and Toru Yuki (結城亨) was the producer. It can be said that they were the “court” sound engineer and music producer, respectively, for Denon (Nippon Columbia). Aoyama Tower Hall (Japanese: 青山タタワーホホール) is a medium-sized concert hall located near Gaienmae Station. Located in Junzo Yoshimura's Aoyama Tower building, it seated approximately 220 people and was mainly used for classical and jazz concerts. The hall was opened in 1969 and closed a few years ago. The venue was popular with both classical and jazz music publishers, to mention, for example, Three Blind Mice, which often hosted its projects there; more → HERE. The Smetana Quartet (Czech: Smetanovo kvarteto) was a Czech string quartet that existed from 1943 to 1989, although it was not known as the Smetana Quartet until 1945. Its lineup was exceptionally stable. The album in question features Jiří Novák (first violin), Lubomír Kostecký (second violin), Milan Škampa (viola), and Antonín Kohout (cello); Kostecký and Kohout were the only members of the ensemble who played in it from the beginning to the end of its existence. The 1972 session was the ensemble's third in Japan after a ten-year absence.

This record has the catalog number OX-7008-ND, which suggests that it is only the eighth “digital” recording of this release. In fact, it was the first recording made on the DN-023R tape recorder to be made public, but it was released after seven later recordings. It is therefore the fourth recording in history with a digital recording, after the three experimental ones we mentioned at the beginning. |

The album was released in a single sleeve, with an appropriate obi strip indicating the recording method – PCM Denon. This was repeated in large blue letters on the label; this color was reserved for classical music recordings, while jazz was given the color red. The version we are listening to is from 1975. The album was originally pressed using the Master Sonic technique, but the reissue was not. ▌ Sound THE SURPRISING THING, at least when listening to Denon's digital recordings for the first time, is how clearly you can hear the air noise of the room in which the recordings were made and how natural it sounds. This is normal for classical music recordings, but let's be honest, it is usually masked by tape noise. Here, the transition from the run-up to the groove with the recorded data is clear and unambiguous. This is also excellent news when it comes to pressing – it is quiet, with almost no noise or crackling – despite the fact that more than fifty years have passed since the release of this album!

The second thing that may surprise you is how “vintage” the sound is. The sound is based on the midrange, closer to 600 Hz than 1 kHz. The extremes are clear and distinct, but the greatest energy is found where tube devices, mainly microphones, usually boost the sound. We do not know the details of the production of this album, as is the case with most Denon albums, so perhaps one of the classic microphones, such as the Neumann U67 or Neumann U47, which are currently used by, for example, the Tacet label, was used for the recording; more → HERE. The recording was made in Aoyama Tower Hall, which is a relatively small room. So there isn't much reverberation here, and either the engineers didn't use any external reverb devices, or they did so very subtly. The sound is therefore rather direct, rather dry and without a long “tail,” similar to what we know from archival recordings often made for radio in the 1920s-1940s. Sometimes, as at the beginning of Adagio, in E-flat major, you can hear the not-quite-edited end of an announcement, either from the studio or from one of the musicians. And it is only this announcement that evokes a rather long but dark reverberation. This contributed to the clarity of the presentation, even though the last thing that can be said about it is that it is “clear.” And that is probably what people asking about digital technology wanted to know. Denon's recordings never, ever resemble what computer technology has done to digital sound by brightening and lightening it up. The production of the album I am talking about is extremely balanced, even dark, but not because the upper treble has been cut off, but because it is well proportioned with the rest of the spectrum. Interestingly, the sound of the album Something, recorded in 1970 on an NHK prototype, was more heavily weighted in the upper range. ˻ II ˺ EARL „FATHA” HINES Solo Walk in Tokyo Nippon Columbia NCP-8502-N

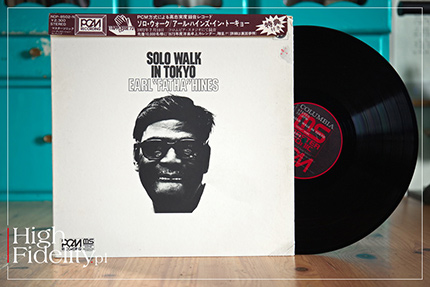

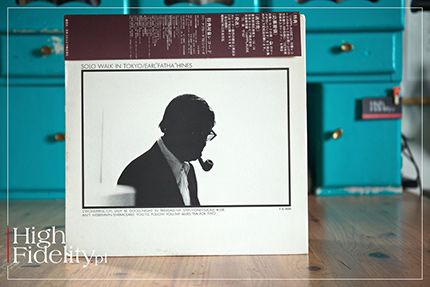

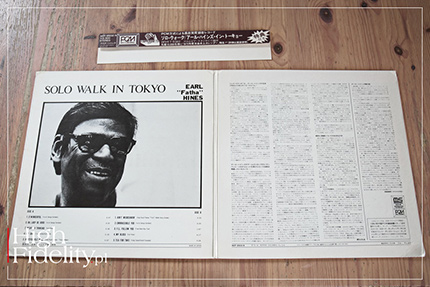

EARL “FATHA” HINES was an American jazz pianist and band leader, known mainly in the 1940s and 1950s. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, “one of the few pianists whose playing shaped the history of jazz.” He made his first appearance in Japan relatively late, in July 1972, at the age of 66. However, as we read in the essay accompanying this edition, “he looked young and impressive, and when he appeared on stage, he showed no signs of slowing down.” The album was recorded on July 10, 1972 at Studio 2 Nippon Columbia during Hines' stay in Tokyo. Usually, recordings of this type took three days to complete, but this time, because it was to be a solo album, the whole thing took an hour and a half – recording began at 1:00 p.m. and ended at 2:30 p.m. All recordings were first takes, played live – the pieces were not repeated.

This is a prestigious Denon project, which is why the vinyl featured a double, luxurious cover. This release was intended for sale only in Japan, which is why it bears the Nippon Columbia logo, and the label says “Columbia” instead of “Denon.” The obi is placed differently than usual, at the top. This was to help buyers in stores quickly familiarize themselves with the contents of the album while browsing in a record store. ▌ Sound The copy of the Hines album that I own is in slightly worse condition than the Mozart pieces played by the Smetana Quartet – it crackles and hisses a little more. But even in this comparison, it is a very quiet pressing. And extremely similar in aesthetics to what I heard in the Mozart recordings. That is, a sound based on the midrange. The Denon DL-103R cartridge, which has a tendency in this direction, helped in this perception, but it did not cover up the recording itself, because a very similar sound repeated when I listened to it with the Miyajima Lab Destiny cartridge. I am talking about a distinctly dark sound. And again, not dark because of the high frequencies being cut off, but because of a kind of emphasis placed on the lower midrange. As with the classical music recording, this recording also presents the instrument from a certain distance, without long reverberation. It is as if the engineers wanted to use as little signal processing as possible before recording it on the disc. And there is no question of the close sound that dominated piano recordings in jazz and classical music, where microphones are placed under the lid and under the soundboard.

Here, the whole thing sounds like it was recorded with a pair of stereo microphones placed at a certain distance from the instrument. I could hear the musician accentuating individual phrases, transitions, and tempo changes with sighs, sometimes even murmurs. These elements do not dominate the music in any way, but are rather something “beside” it, part of the mystery, something that adds emotional depth. Let's repeat: it is a dark, dense sound with a direct, almost monophonic perspective. Its dynamics seem strong, but because the microphones are positioned far away from the instrument, the contrasts are not exaggerated. We get the impression that the sound engineers wanted to showcase the silky smoothness of the sound rather than contour it. In the 1980s and 1990s, we will witness the opposite trend, which will lead to a caricature of the sound we collectively call “digital.” Here, it sounds as if the sound of a roller has been combined with tin foil and the precision of a tape recording. Digital? – It is clear that we have lost several decades to catch up with what the Japanese were doing in the 1970s and, ultimately, to surpass it. ˻ III ˺ EUGEN CICERO My Lyrics Nippon Columbia NCP-8503-N

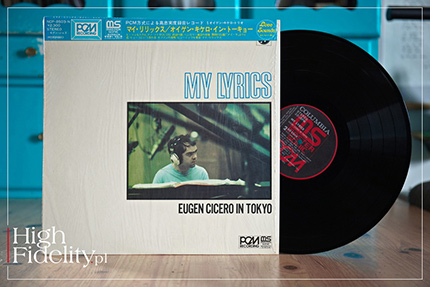

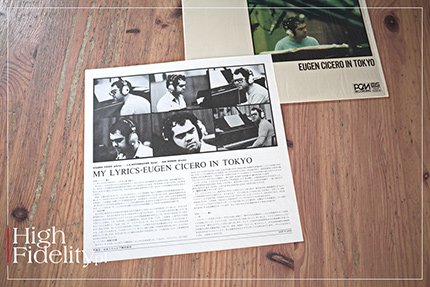

AS WE READ IN HIS BIOGRAPHY, Eugen Cicero (born Eugen Ciceu; 1940–1997) was known as “Mister Golden Hands.” He was a Romanian-German jazz pianist who performed in a mixed classical-swing style. Born in Vad, Romania, to Teodor and Livia Ciceu, an Orthodox priest and a professional singer, he began playing the piano at the age of four. At the age of six, he performed Mozart's piano concerto with the symphony orchestra in Cluj. Wikipedia adds that after graduating from the conservatory, he abandoned his career as a concert pianist and that his own style was somewhere between classical and jazz piano, as he introduced swing harmonies into Baroque, Classical, and Romantic compositions, often in the form of spontaneous improvisations. The album My Lyrics was recorded in a single day, on July 23, 1972, at Nippon Columbia Studio No. 1 in Tokyo, and released in November of the same year. The album features a trio consisting of Eugen Cicero on baby grand piano, Johann Anton Rettenbacher on double bass, and Dai Bowen on drums. In an essay accompanying the album's release, the recording director, Takuo Morikawa, writes:

The album was released in two formats – as a gatefold and a single; we are showing the latter. In both cases, it featured obi strips attached from above – cap obi. Inside, we find a printed insert with descriptions of individual tracks. The disc was pressed using two of Denon's flagship techniques from that time – Master Sonic and Half-Speed.

The first involved reducing the size of the groove so that the cutting head needle would move in the same way as a turntable stylus. This was to prevent the needle from moving during playback along the lower part of the groove, where there is no information, only noise. Some of the Non-Distortion Cutting records were additionally recorded using the Half-Speed technology. This technology, known from many later audiophile releases and currently celebrated at Abbey Road Studios, involves playing the tape twice as slowly and cutting the lacquer in this way. This results in significantly lower distortion and a wider frequency response. ▌ Sound EVERY TIME I hear a new recording from Denon, made on tape recorders whose resolution we would today describe as “ridiculous” or even “embarrassing” – in this case, let me remind you, a whole 47.25 kHz sampling frequency and 13 bits of resolution – I understand people who for decades refused to accept digital recordings. Compared to what we hear on Eugene Cicero's album, the 1990s and much of the 2000s seem lost – not always, but still.

The sound of the record in question is wonderful because it is naturally large and present. The piano, shown up close, is neither glassy nor aggressive. The double bass, positioned in the right channel, has a strong slam and excellent selectivity. But it is also dynamic and energetic, without the fattiness that muddies its sound on many analog recordings. The drums are shown at a certain distance, so they are not immediate. Perhaps that is why the cymbals sound so great here. They are resonant, have weight, and are not “dry.” The piano opening ˻ A-3 ˺ Impression Of A Hungarian Land Scape has a very nice depth, even though it is presented almost monophonically, on the listening axis. When Cicero strikes harder, when he attacks the instrument, we get a bigger picture, without it imposing itself on us. It is an extremely organic sound, aided by great bass and very nice percussion. You can hear that the instruments were placed either behind an acoustic screen or even in a separate room, because they are strongly acoustically isolated from each other and from the piano. But it comes across very naturally, nicely. In the last tracks on the album, for example in ˻ A-4 ˺ Chorus Of Victory (From "Aida"), the acoustic response of the interior is more audible in the sound of the drums – so perhaps it was not placed separately, but only isolated from the rest of the band by partitions. The sound of the cymbals is reflected in the right channel, in the double bass channel, which plays here in a richer and deeper way than in the previous tracks.

Sometimes, as in ˻ B-1 ˺ Hana, the piano touches on a more penetrating sound. However, it does not exceed good taste. At the same time, it sounds clear, which is not always the case with analog recordings. In the next track on the album, ˻ B-2 ˺ And If You Find That You'd Call Her Kyoko, this is corrected towards a darker sound, although here too it is a powerful sound at times. But in this track, the double bass solo is more important. If we want to hear what Denon's digital tape recorder offered in terms of tone, selectivity, and clarity, this is a good moment. It's great music, excellent musicians, and perfect production. If we could record like that today, we'd be happy. But that's the advantage of a perfectionist approach and the fact that there wasn't much “fiddling around” here, that it was actually a “100%” recording and that it was controlled by people who really cared about combining music with sound. ▌ Summary It is still impossible to accurately trace the processes that led to the creation of the first digital tape recorders due to scarce source materials. Language and cultural barriers are also a problem. Although we have several documents at our disposal, usually part of panel presentations at Audio Engineering Society (AES) conventions, this is still not enough. Much of this information is not confirmed in documents, but is a compilation of the memories of the sound engineers, electronics engineers, producers, and directors who participated in them. And, as we know, memories and biographies are not very reliable.

⸜ Initially, Denon did not elaborate on the technologies they used, merely noting on the inserts that it was a digital recording and informing listeners which tape recorder was used to make the recording. Over time, more and more information was provided, until finally, at the end of the 1970s, with the advent of the U-Matic tape recorder, this information disappeared from the disc descriptions. That is why even the most well-known articles and materials discussing the first decade of this ferment, including my early articles on digital systems, need to be corrected with new information from time to time, and enriched with newly discovered details. This is how science works in practice, as a self-regulating and self-correcting “machine.” Despite my sincere intentions (truly sincere) and the time (five years) and work (countless hours) I have devoted to exploring this topic, I still have to correct myself. However, I believe that even in this form, it is worth sharing this information. Returning with you to Denon's early years in digital recording, I had to rewrite this story in many parts. I hope you will agree with me that it was worth it. As it turns out, it is an even more fascinating story than the one that was told at the time – richer internally, more feisty, and more powerful. It involves incredible amounts of money, enormous ambition, the enthusiasm and passion of the people involved, and above all, wonderful music recorded in a way that is rare even today.

⸜ The development of the smaller, lighter DN-23RA tape recorder enabled Denon to take digital recordings out of the studio and travel to Europe—Paris, Stuttgart, Prague, etc. The first two parts of this article dealt with the world's first digitally recorded LPs, first using an experimental NHK tape recorder, and then the first Denon tape recorder, which in turn produced the first classical music record in history recorded on digital equipment. The next, third part will focus on the DN-23RA tape recorder, which allowed Denon engineers, and later also producers from the Czechoslovakian label Supraphon, the French label Erato, and others, to record outside of Japan and outside of the studio. I would like to invite you to part three, covering the years 1974-1977! » HF ▌ Bibliography

⸜ Entry „Digital recording” in: Wikipedia, → en.WIKIPEDIA.org, accessed: 6.10.2025.

⸜ HIROSHI IWAMURA, HIDEAKI HAYASHI, ATSUSHI MIYASHITA, TAKEAKI ANAZAWA, Pulse-Code-Modulation Recording System, AES Journal Volume 21, Number 7 pp. 535-541, September 1973.

⸜ General Catalogue. 1980/81. Denon source: → www.CIERI.net, accessed: 2.10.2025. |

main page | archive | contact | kts

© 2009 HighFidelity, design by PikselStudio,

projektowanie stron www: Indecity